First Game Digital Game Designer

One of the first video game programmers was a young woman who'd recently graduated from high school.

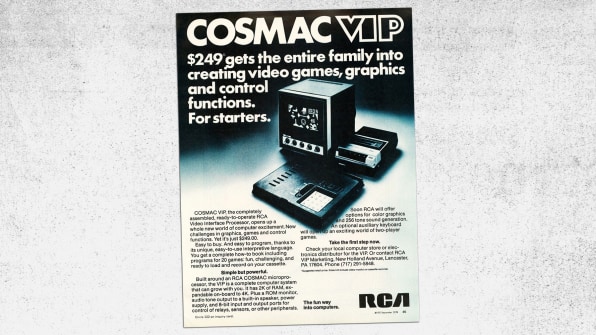

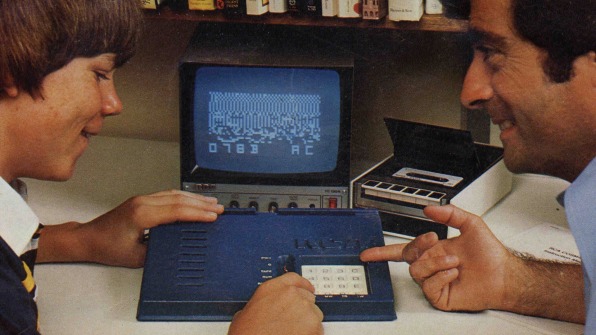

Forty years ago, consumer electronics giant RCA released the Studio II, a programmable video game console that, along with the Fairchild Channel F, pioneered the use of ROM cartridges as interchangeable game media.

RCA's console never rivaled the impact of Atari's VCS, Magnavox's Odyssey, or Mattel's Intellivision, and few people remember it today. But the true story behind it is fascinating. Its underlying technology began in 1969 as a personal computer developed at home by one man with a vision, Joseph Weisbecker. His daughter, Joyce, ended up being the earliest known female developer who wrote video games and got paid for it.

Joyce Weisbecker's work—which I was alerted to by a fellow tech historian, Marty Goldberg—is so little known that back in 2011, I declared Carol Shaw, who worked at Atari beginning in 1978 and later designed Activision's classic game River Raid, to be "the first female professional video game designer." Though Shaw's work remains historically significant, it turns out that Joyce Weisbecker's work predates it by roughly two years.

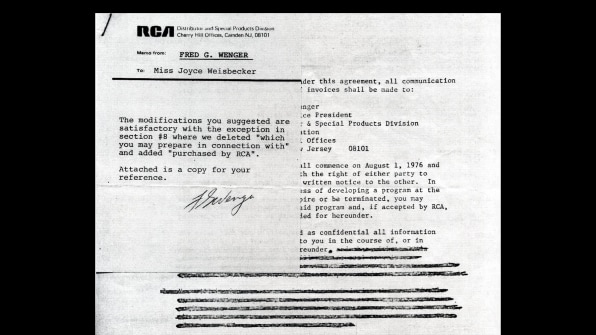

And she accomplished it without ever being on staff at RCA. "I know there were no other women at RCA doing the programming," she says today. "A couple of guys did and they were employees. I think I was the only person outside the company that actually got paid to do a video game. So I was the first contractor . . . and possibly the first independent video game developer, because I came up with the idea and pitched it, and they said okay."

Engineering In Her Blood

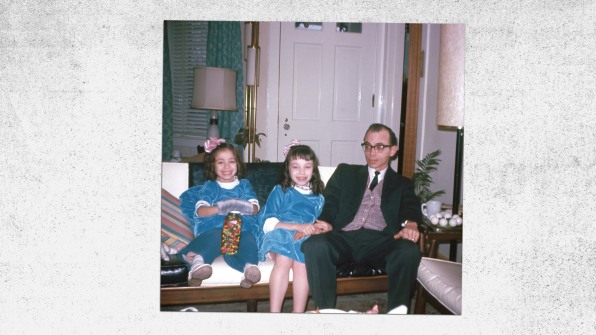

Joyce Weisbecker was born in New Jersey in 1958. During her childhood, she recalls watching her dad, a relentless hobbyist, develop logic games, devise stage illusions for local magicians, and build electronic inventions in his basement when he wasn't working by day at RCA. Her mother, Jean Ann, was a third grade teacher who emphasized the value of education and encouraged her eldest daughter to pursue what came naturally to her.

Whenever she got a chance, Joyce would tag along to her father's office at RCA to see what was in development. There, the engineers looked kindly on the girl, who seemed to naturally absorb everything presented to her, including a prototype billiards video game developed by playful RCA engineers in the mid-1960s.

Aside from his engineering job at RCA, Joseph was fascinated by the future of computers, a field he became entranced by after reading a seminal 1949 book by Edmund Berkeley, Giant Brains, Or Machines that Think. Joyce tells a story about how, in the fall of 1955 when her parents first met, her father told her mother that some day computers would be drastically miniaturized and built into practically everything–refrigerators, typewriters, and ovens.

When Joseph first became enamored with computers, they existed primarily as vacuum tube-powered behemoths requiring the electricity of a small city to operate. So the elder Weisbecker experimented heavily with computational tricks that anyone could perform on paper–in the 1960s, he even created a paperback book that played Tic-Tac-Toe against you depending on which page (and thus which move) you chose.

As technology improved, Joseph began experimenting with computers at home. A firm called Heathkit sold a wide range of electronic gadgets and appliances that anyone could order unassembled and build themselves. "He wanted to buy a Heathkit to build a computer," says Joyce. "But since there weren't any available, he decided that it was his goal in life to design a Heathkit for computers so that anyone could buy and build one."

At the time, a typical minicomputer might cost anywhere between $6,000 and $25,000. (To put that in perspective, the average yearly income for American families during 1972 was $11,286.) Working at night for hours in his home's basement, Joseph designed a complete computer system himself, including a custom central processing unit, out of discrete components and circuits.

Joyce recalls accompanying her father on visits to Radio Shack stores in 1969 to purchase parts for his computer prototype. He had to visit four different stores to get enough switches and parts to make a front panel for his computer, which had eight switches, one for each instruction bit. Along the way, he kept quiet about his plans so he wouldn't arouse suspicion from the store owners, who would inevitably delay him with queries about building a home computer–a fantastic, crazy idea at the time.

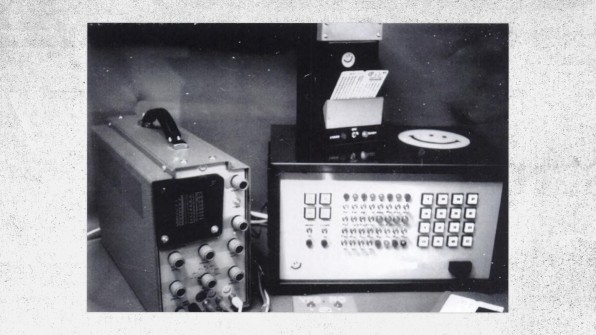

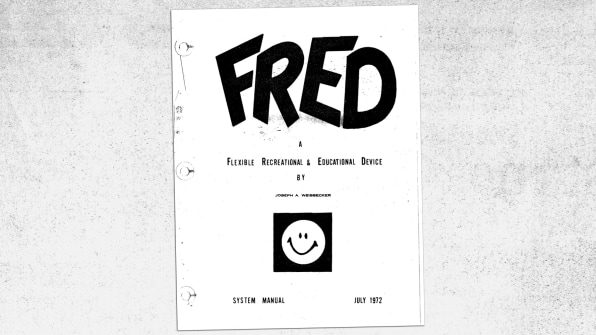

As he neared completion on his first home PC prototype, Joseph decided to call his computer FRED, or Flexible Recreational Educational Device. He gave it a smiley-face logo and continued to work on it throughout 1970, 1971, and 1972, all on his own dime.

From FRED to Studio II

After development of FRED concluded in the basement, Joyce's father set up his machine in the back enclosed porch just off the dining room of the family's 1,300-square-foot house in Cherry Hill. Soon both Joyce and her younger sister, Jean, found themselves playing with it, encouraged by their father. And Joyce even began programming it.

"It was a natural interest," she recalls. "Dad showed my sister and me how to do it. My sister was more into taking horse-riding lessons. But I thought, 'This is like really cool puzzles. It's just that puzzle nature–it either gets you or it doesn't.'" It definitely got Joyce, who had been one of the few in her high school to learn how to use the school's programmable 100 step calculator.

The FRED machine came to the attention of Joseph Weisbecker's managers at RCA, but they were skeptical at first. In the early 1970s, RCA had just left its golden era with the retirement of its charismatic long-term leader, David Sarnoff. His resignation left the company rudderless as his son Robert guided RCA in myriad directions, including purchasing rug companies and chicken farms. On top of that, RCA had recently been burned by an unsuccessful foray into taking on the mainframe computer market, resulting in a multimillion dollar write-off.

Around 1973, RCA turned its attention back to computers, and Joseph's home-built FRED 8-bit computer architecture became part of an official project to build a complete computer on a chip. This resulted in the Cosmac 1801 series, a two-chip microprocessor system first made commercially available in 1975. (It was then refined into a single chip, the Cosmac 1802, released in 1976.) RCA management steered the project in the direction of embedded computer control for industrial applications, but the elder Weisbecker never gave up his dream of creating an educational computer for the masses.

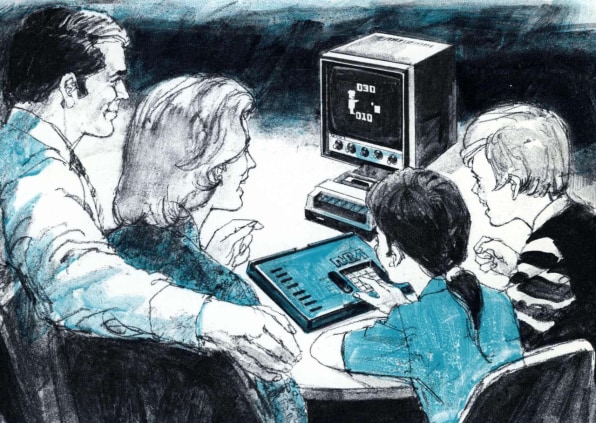

About the time Atari's Pong was burning up the arcades, Joseph tried to sell RCA on the idea of making a programmable home video game console, but management had little interest in the idea at first. Instead, the FRED technology made its way into a prototype coin-operated arcade video game cabinet with interchangeable software titles around 1975. That project fizzled out quickly. But eventually, Joseph's efforts resulted in several home computer products, including a build-it-yourself PC called the Cosmac VIP and the Studio II game console.

"They dragged their feet for like a year to decide they wanted to be in the home business," says Joyce Weisbecker. "And then it took them a little more than a year again to actually get the thing out. And that's bypassing the FCC certification."

Though the Studio II wasn't announced until January 1977–a couple of months after Fairchild's Channel F had hit the market–the technology, including games on cartridges, was ready as early as 1975, according to Joyce. "I guess I get a little bitter about that," she says. "He could've been the first."

Weisbeckers At Work

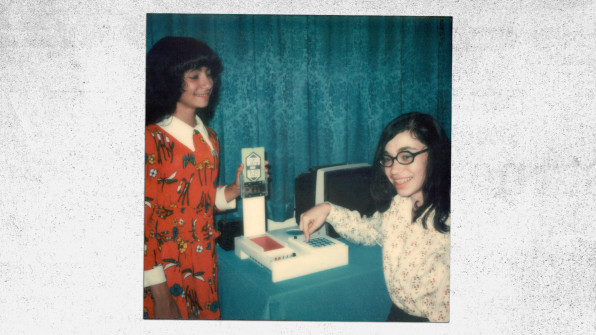

The arrival of home electronics products based on her father's work provided an opportunity for Joyce, who had recently graduated from high school. In the summer of 1976, while she was on break before her first semester at Rider University, Joseph asked her if she wanted to program video games for RCA.

Having ample experience with her dad's machine already, she plunged head-first into programming demonstration games for the RCA Cosmac VIP, the inexpensive commercial computer kit based on Joseph's FRED designs that served both as a primitive home PC and a development kit for Cosmac 1802 CPU applications.

Snake Race and Jackpot marked Joyce's RCA programming debut, although she did not get paid for the work. Her father ran the VIP project on a shoestring budget. RCA included the software she wrote as program listings in the VIP manual, to be keyed in manually by the machine's owner.

But soon Joyce would earn her first paycheck from RCA. As work on the Studio II home game console geared up, the firm began looking for software. RCA employee Andy Modla ended up programming most of the Studio II's 10 cartridge releases, but the elder Weisbecker saw this as a good opportunity for his daughter to get more coding experience.

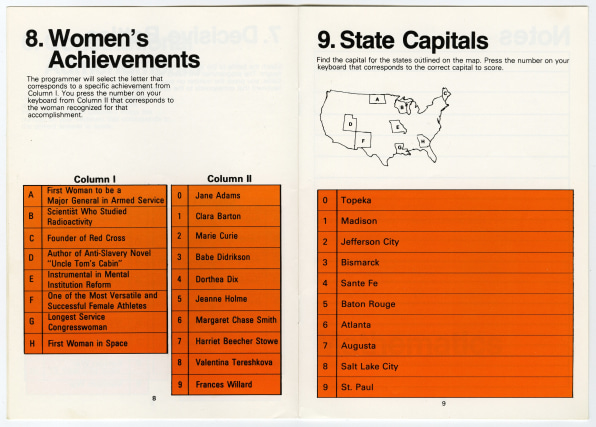

As for the subject of his daughter's console debut, Joseph turned to his favorite focus: education. Seeing the Studio II as an inexpensive home computer as much as a game console, he advised RCA to utilize its connection with the education textbook business of its subsidiary, Random House. (The publisher was one of the tangentially related firms acquired during RCA's wild and wooly period of business diversification.)

One day in August, Joseph came home and said, "They're looking for someone to do a quiz on the Studio II. You want to do that?"

"Sounds boring," Joyce replied.

"Get it on your résumé, and you're getting paid for it," he said.

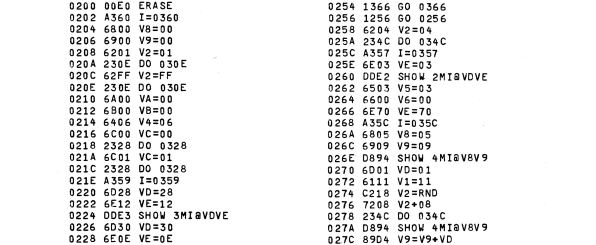

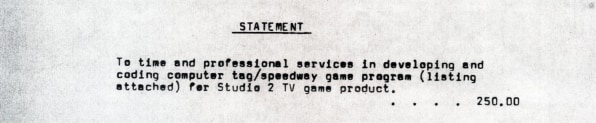

That began a project called TV Schoolhouse I, programmed in early August 1976 and delivered to RCA on August 9 for a payment of $250, according to the invoice which Joyce kept. It had taken her about a week to program the simple game, working at one of her father's FRED prototypes, using pen and paper to write assembly code and then entering her work using a hexadecimal keypad, one instruction at a time. Unlike her earlier programming for RCA–which gained her a credit in the Cosmac VIP manual–she did this work anonymously.

TV Schoolhouse I was a two-player computer quiz that relied on supplemental printed question books that came with the cartridge. Each player would take turns reading a question in the booklet, then typing in a multiple-choice answer on the Studio II keypad. The program would check for the correct answer and keep score, tallied on screen.

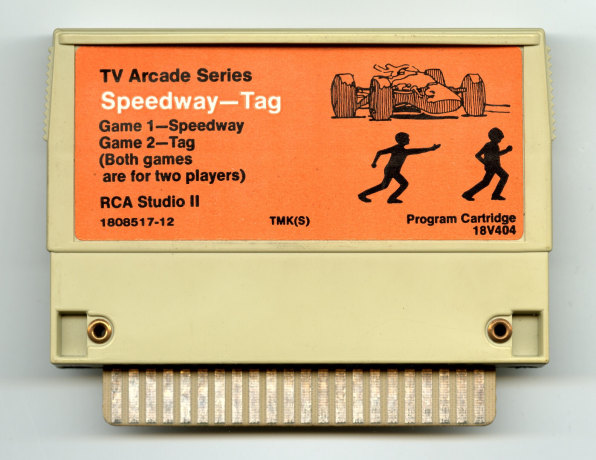

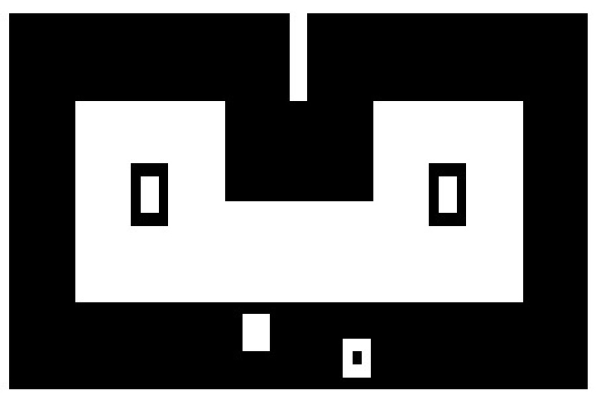

In October of 1976, Joyce programmed two action games: Speedway and Tag. In Speedway, the player pilots a small car on an overhead racetrack verses a second human player. There was only one problem: The Studio II's extremely low graphical resolution of 64 by 32 pixels left very little room for detail.

"People who work with modern computers don't understand the restrictions," says Joyce. "The hard part was not fitting the code in 2K or running on a slow processor–there's plenty of things you can do with that. The problem was how do how could you display the state of the game on such a limited thing? You had the equivalent of two black-and-white 32-by-32 Windows icons, and that was your entire screen."

Those limitations explain why, in Speedway, Joyce chose to represent the race cars with two white squares, one of which has a black dot in the middle. "People criticize: 'Oh, yeah, it doesn't look like a car whatsoever,'" she says. "You try doing it! You know? You try making an entire game that fits in two Windows icons."

Joyce's Tag is an even more stripped-down affair. In this two-player game, each player controls a simple spot on the screen. One player is "it;" that player must guide their spot away from the other player's spot so they don't touch. Each game is two minutes long and whomever has the most points (each touch is worth 10 points) wins the game.

Tag represents nearly the simplest video game one can play with two spots on the screen–coincidentally, a similar game had been the first-ever TV-based video game, created by Ralph Baer and Bill Harrison at Sanders Associates in 1967 (Baer called it "the chase game").

RCA released the two games on one cartridge, a choice that came from Weisbecker herself. "I had room left over on Speedway, and Tag was too simple to put on its own cart," she recalls. "And I wanted to increase the chance that RCA would buy my race car game."

RCA did buy it, as evidenced by an invoice, dated November 28, 1976. She says these two games took her about 200 hours of work. "I sent in the code in October and billed them, but apparently either they didn't like it or I realized I could've made it faster," she recalls. "In November, I sent them a revised version, and that's the one they published."

When considering the historical significance of these games, one must remember the Studio II's limitations–and that these early titles originated from someone fresh out of high school at a time when very few Americans owned or interacted with computers. Of course, she had already been programming on one of the world's first home computers for several years by then. The world would soon catch up: By the end of 1976, 40,000 personal computers would be sold in the U.S.

Failure To Launch

Having failed to beat the far more capable Fairchild Channel F to the market, the Studio II was already obsolete at launch. Atari would release its soon-to-be console juggernaut, the VCS, later in 1977.

Aside from the low resolution, one of the Studio II's key drawbacks was its built-in, Touch Tone-like keypad controller, with no option for a joystick. Joyce gives multiple reasons for the keypad, including a quest to lower the manufacturing cost to hit a $150 price point, and the fact that RCA (and Joseph Weisbecker) intended the Studio II to be a stopgap machine until its planned successors launched. These included a color-equipped Studio III game console, an intermediate Studio IV home PC, and a full-fledged Studio V computer. "When you have a full-color screen with good resolution, yeah, you put a joystick on it," says Joyce. "That's for a later iteration and with a home computer or a deluxe video game system, if you ever get there."

As a result of its technical limitations and limited game library, the Studio II sold poorly, and RCA pulled the plug on the product after just over a year, in February 1978.

Joseph Weisbecker found himself stymied and frustrated, holding many plans for educational computer products that would never see the light of day. But for RCA, these consumer electronics products themselves had always been a secondary consideration: "RCA management never wanted to get in the video game market," says Joyce. Instead, they were merely looking for a market for their semiconductors.

And judged by that goal, the 1802 CPU was a massive success. While it never fared well in entertainment and home computer products, it went on to find use in automobiles, pacemakers, and even space probes (like Galileo, launched in 1989, which explored Jupiter and its moons). A version of the chip–containing the same computer architecture designed by Joseph Weisbecker for his home computer in 1969–is still manufactured today and praised for its fault tolerance and physical hardiness.

Owing to the short lifespan of the Studio II, Joyce's association with the console ended quickly. "They never sold enough of the games to ever come back and ask for more," she says. She never got a chance to see her first commercial game products on retail store shelves, but she did get a copy for herself.

Life After RCA

In 1977, still under contract with RCA, Joyce programmed three games–Slide, Sum Fun, and Sequence Shoot–for a commercial supplement to the VIP's included documentation called the RCA Cosmac VIP Game Manual. Just after that, her contract expired. When the time came to decide whether to keep pursuing game development, she decided to instead focus on school, picking stability over the uncertainty of forging ahead in the rapidly growing early home PC game market.

"You look around and you say, 'Okay, do I really want to live at home and spend every night duplicating cassettes, and going down to the post office and making photocopies of the instruction manual, and coming home and putting them in little plastic Ziploc bags and mailing them off to people?'" says Joyce. "That was the computer game industry at the time."

Joyce continued her college career at Rider until she earned degrees in computer engineering and actuarial science in 1980 as a double major. She pursued a career as an actuary, inspired in part by her father's idol, Edmund Berkeley, who had done the same. In 1998, she went back to school to get a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering and a masters in computer science, and she worked for a time as a radar signal processing engineer designing digital filters. And in recent years, she's become interested in game devopment again. "I'm trying to gear up to do really interesting AI and computer-assisted animation," she explains. "Because I realize I want to do story-based cooperative games."

As for her father, Joseph continued at RCA until 1982, when emphysema made it dangerous to drive to work. He insisted that the damage to his lungs came from years of inhaling resin smoke while soldering projects in a tiny room of his home's basement. "It was his Radio Shack flux," recalls Joyce. In retirement, he remained a hobbyist and was a devotee of video games–especially The Legend of Zelda. He died in 1990.

Looking back, Joyce Weisbecker does not particularly want to be known as the first female video game developer. To her, that is merely a coincidence. Instead, she considers herself possibly the first "indie" video game programmer, since she was an independent contractor and not an employee of RCA.

Still, she underplays her role as a tech hero. Upon my first inquiry into her history, she was immediately thrown off by my focus on her own achievements. "You're the first person to ask about my work," she said. "And I was only prepared to talk about my father's work with me as a footnote."

Well, I'm here to say that Joyce Weisbecker is definitely not a footnote. For every Steve Jobs and Bill Gates in tech history, there's a forgotten pioneer like her. And by commemorating her accomplishments of the 1970s, when the market for home video games had barely gotten underway, we can help pave the way to a more inclusive future for the engineers and scientists of tomorrow.

First Game Digital Game Designer

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90147592/rediscovering-historys-lost-first-female-video-game-designer

Posted by: chamblisswaregs.blogspot.com

0 Response to "First Game Digital Game Designer"

Post a Comment